The text and images below will appear on an academic poster that I am presenting at the Impact 8 International Printmaking Conference in Dundee, Scotland later this year. The conference theme this year is “Borders and Crossings: The Artist as Explorer.” My poster responds to this theme using my latest suite of prints, Feral Family Portraits, as a spring-board to provoke discussion about making art within a cultural legacy of colonial violence. To purchase the prints from this series please visit http://www.etsy.com/au/shop/RachelJoyPrintmaker.

Exploring our feral hearts:

non-indigenous artists and the legacy of colonial violence in Australia, a multi-disciplinary approach.

Bullocky.

Wood engraving and digital print.

From an Australian perspective the idea of exploration is, or at least should be, fraught. Exploration implies the discovery of the unknown. Certainly, there was plenty that was unknown to Europeans when they arrived in what would become known as Australia. The seasons were back to front, the animals were outrageous confabulations, the trees shed their bark not their leaves. None of it made sense to European minds but instead of asking the locals how it worked they murdered them then pretended they didn’t exist and stole their land. Today’s psychology journals would describe such behaviour as sociopathic.

Australia was built on the lie of “terra nullius” the concept of an empty land. This was a convenient lie the British colonists told themselves in order to justify their thievery. The Australian Government’s continued categorisation of indigenous Australians as native fauna until the 1967 referendum is evidence of just how far the self-deception went and for how long.

Historically European explorers set off into territory that was, to them, unknown. Many found the land hostile and difficult to negotiate, some even perished because they didn’t seek the help or heed the advice of those for whom the land was deeply known and understood.

What was the purpose of European exploration? Sometimes, perhaps to understand (for scientific purposes and to fulfil that peculiar European desire to collect and categorise) but more often it was to assess its potential as grazing land to be possessed and exploited for material gain.

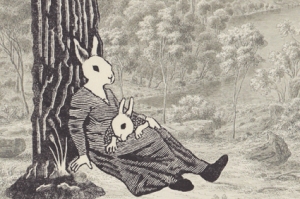

Feral Family Portrait.

Wood engraving and digital print.

When thinking of exploration one might imagine crossings such as fording a river, traversing a desert or mountain range in a romantic quest for an Aussie El Dorado or equally improbable inland sea. In Australia these are the crossings our pioneers are famous for. We’d rather not talk about crossing the line of human decency with invasion, land grabs, genocide, child stealing and racism.

White Australia would do well to explore its own soul in an attempt to understand the mentality, the collective psyche, if you’ll allow, that perpetrated the evils of colonialism and then denied it ever happened. In some parts of the world today holocaust denial is again rearing its ugly head; in Australia we built a nation on it.

Printmaking has often been political and its many low cost incarnations make it a very versatile and democratic medium. Printmaking has become a powerful medium in the hands of indigenous Australians with many dedicated studios emerging to sustain this interest. However, as a white artist engaged in a multidisciplinary art making practice I see printmaking colliding with sculpture and street art to create something both beautiful and challenging. My work is an attempt to engage in a meaningful public dialogue about the constructed nature of our history and sense of community.

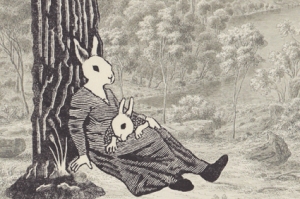

My latest project Feral Family Portraits explores notions of the foreign, outsiders/insiders and the feral. It posits European Australians as the ultimate feral animal. Using a combination of wood engraving and digital print technology I have created images that strongly reference and borrow from iconic colonial landscape and portrait paintings and photography. The original colonial images were created to represent a construction of truth about the colonial experience. By replacing the heads of the protagonists with those of feral animals I hope to re-present another truth regarding colonial experience.

Madonna and child on the wallaby track.

Wood engraving and digital print.

This project challenges the idea of exploration as a heroic or noble endeavour and posits it, within the context of Australian colonialism, as a rather more fraught element in the construction of our national identity. Drawing inspiration from Theodor Adorno’s famous quote about the difficulties of making art after the holocaust, the goal of the project is to acknowledge the genocidal nature of the Australian colonial experience and ask how non-indigenous artists can make work that recognises this history and its ongoing implications.

Contemporary Australia has a fragile fragmented identity but it sometimes comes together in beautiful and unexpected ways. A multidisciplinary approach to making art reflects this and by opening up the process allows exciting possibilities to emerge. My own practice of colliding printmaking with sculpture and street art underscores the value of taking print out of the gallery and onto the streets. In particular the recent suite of prints and printstallations Feral Family Portraits, shows how the multidisciplinary approach of the work aids in exposing the constructed nature of our history and sense of community.

Billy Tea.

Wood engraving and digital print.

One incarnation of the project involves the works being installed as life-sized paste-ups in locations around my city (Melbourne) that have relevance to each particular image. For example, the work Bullocky has appeared on walls on the site of the former stock and sale yards in Kensington and Angler has graced the arches of the Queen Street footbridge over the Yarra River. Bullocks were the beast of burden most relied upon to pull the cartloads of materials required to open up and settle the land and European Carp were introduced to the rivers for sport, as a food source and reminder of “home.”

Angler.

Wood engraving and digital print.

The project highlights the importance of the social and historical value of the sites chosen to install the work and the democratic nature of a public viewing space. It also asserts the role of humour in drawing an audience in, to consider the deeper elements of emotionally challenging works. Here I would draw your attention to Bakhtin’s theories around the carnivalesque and it’s role in upsetting power dynamics. There are many examples of subaltern groups making use of humour to draw attention to injustice and my project continues in this vein.

Trapper.

Wood engraving and digital print.

Powerful art should cross boundaries and explore ideas. So to that end I am taking this opportunity to problematise one possible reading of the conference theme in an effort to open up discussion about the issues faced by non-indigenous artists who acknowledge an inherited legacy of colonial violence.

References and further reading

Adorno, T. Aesthetic Theory, Continuum International Publishing Group, 2004.

Anderson, B. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the origins and spread of nationalism, Verso, London, 1993.

Bakhtin, M. Rabelais and His World. Indiana University Press, Bloomington, 1984.

Grimshaw. P, Lake. M, McGrath. A and Quartly. M, Creating a Nation, McPhee Gribble Publishers, Melbourne, 1994.

Jung, C.G. Essays on Contemporary Events 1936-1946.

Lake. M and Reynolds. H. Drawing the Global Colour Line: White Men’s Countries and the Question of Racial Equality. Melbourne University Press, Carlton, 2008.

Moses, A.D. ed. Genocide and Settler Society: Frontier Violence and stolen indigenous children in Australian History. Berghahn Books, Oxford. 2005.

Reynolds, H. Dispossession: Black Australians and White invaders, Allen and Unwin, Sydney 1989.

Salzman, L. & Rosenberg, E. eds. Trauma and Visuality in Modernity, University of New England Press, London, 2006.

Schama, S. Landscape and Memory, Fontana Press, London, 1996.

Tumarkin, M. Traumascapes: The power and fate of places transformed by tragedy, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 2005.

Tags: animal, art, Australia, borders, boundaries, british colonists, colonial violence, colonialism, crossings, european explorers, explorers, feral, Impact 8, indigenous, native fauna, printmaking, printstallation, sculpture, site specific, street art, wood engraving