The text below is reproduced from a catalogue essay I wrote for Barbara Beisinghoff’s latest artist book Tau blau Dew blue which will be shown in Bad Arolsen, Germany in the coming months as part of what is perhaps the largest exhibition of her collected works to date.

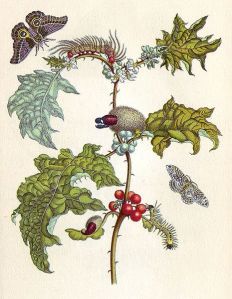

In her creation of Tau blau Dew blue Barbara Beisinghoff reveals herself as an alchemist of the art world, taking base materials, finding in them an inner beauty and revealing them as a precious treasure via a process of transformation at times considered and exacting at others experimental. The printmaker like the alchemist is concerned with the world of chemicals and metals in the forms of ink, plates, resists and acid etches. In Tau blau Dew blue Beisinghoff continues her sensitive attention to materials and processes creating artworks informed by a keen intellect and bringing us a masterfully realised work of delicate beauty.

Sensitivity to materials is central to Beisinghoff’s practice and the handmade nature of the paper itself is highly important to the integrity of the finished works. She comes from a tradition of accomplished craftspeople who value the skill of the hand and her hand is very evident in every stage of the process. For Beisinghoff, paper is not merely a surface to work upon, it is a sculptural medium in itself. Beisinghoff creates her papers both independently and in an active relationship with her paper-maker John Gerard. She treats the newly laid fibres of the pulp as a sculptural material when she turns her water-jet on the work, forcing the water through the pulp and displacing it, creating the forms that will later allow light into the surface. In the case of Tau blau Dew blue Beisinghoff blasts the Fibonacci numbers into the papers. The surface becomes a seemingly ethereal picture plane in itself (something like a tiny cathedral window) when light is cast upon it, illuminating the Fibonacci numbers and revealing their magic and glory.

Much like the stars alluded to in the cross-sections of the flax stems, the watermarks cast and sewn into the pages add a further play of light and thus an additional sculptural and spatial dimension to these works. The three watermarks also refer to the beauty of mathematics as represented in their visual forms and especially as found in the natural aspect of the flax plant itself. The first is the golden ratio showing how the leaf is positioned in relation to the stem so as to allow each one equal access to the sun. The next watermark shows the flax stem as a cross-section and reveals its star-like shape and the fibres within the stem which becomes the paper pulp. The final watermark shows the plant with its seed case reminding us of its connection to the life-cycle and generative properties.

The beauty of mathematics as applied to the natural world is apparent in Tau blau Dew blue as is the value of the spiritual in human life and in our understanding of the world around us. Beisinghoff shares a sensibility with 17th century monk, inventor, and alchemist Robert Fluud who essentially recognised the micro world in the macro or universal when he espoused the belief that for every star in the night sky there was a corresponding plant on earth. Beisinghoff further elaborates on this spiritual dimension to our relationship with the world by accompanying her etchings with text from the Russian poet Marina Zwetajewa. These words describe the growth process through the seasons of a year, through a dew drop on a single morning all influenced by the stars and all knitting together like the teeth of the cogs of some massive mechanical representation of the universe.

The thoughtful attention to detail one has come to expect from Beisinghoff continues in the design and binding of the book. She has chosen a narrow format leporello with sown layers that allude to the swaying of the delicate flowers of the flax plant flexing back and forth in the wind on their long stems. The case acts as a protective seed case enclosing, protecting yet also releasing the gift inside. Tau blau Dew blue is a complex many layered work, the product of much time, thought and labour, it rewards unhurried contemplation and is a beautiful embodiment of the interrelated nature of all things.